Breaking Down Barriers

This research was conducted by Farshore Insight (formerly Egmont Insight).

At Farshore, we are driven to make every child a proud reader and publish in the hope that children will grow up with a reading habit that broadens horizons, deepens empathy, feeds imagination and helps every child achieve their potential. We want all children to have the habit, no matter what their background, and we believe that all reading is good reading. Our broad portfolio, including magazines, annuals, picture books, series fiction, non-fiction and literary novels, offers multiple entry points to help every single child find a way into reading. A culture of reading for pleasure benefits children, our society and the economy.

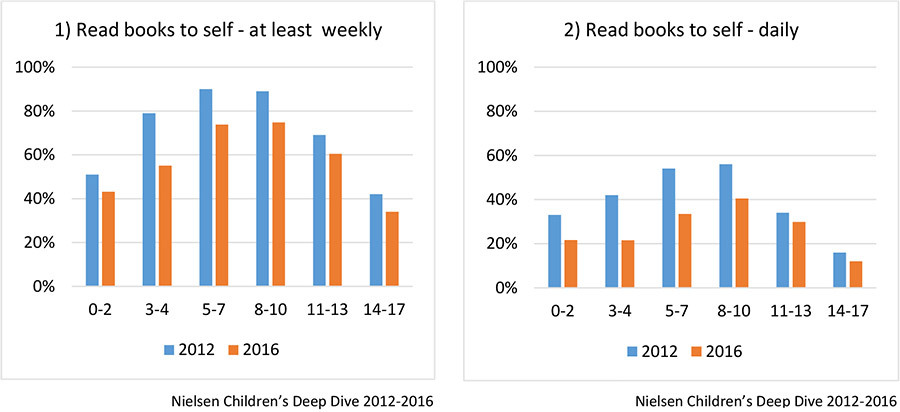

The good news is that the children’s book market is up 7% in value and growing in share so that 24p in every £1 spent on books in the UK is on children’s books [1], and the children’s magazine market is up 5% in value and also growing in share, now at 14% [2]. However, deeply concerning is the declining trend of children reading to themselves.

Why is this? At pre-school age, half of children would rather be doing something active than read books (51%). It’s the same at primary school age (57%), and ‘rather use the internet’ comes in as the second reason for not reading (54%). By secondary school age, preference for the internet is the main obstacle (74%). ‘Books are not cool’ is also a barrier – and at 11-17 years this is stronger for boys (45%) than girls (31%). [3]

By isolating data for children’s participation in different leisure activities and cross-tabulating it against their personal reading, we can see some indication that screen-based pastimes are linked to lower frequencies of children reading to themselves. For instance, in the 8-10 age group, those children who are not weekly YouTube users are much more likely to be daily book readers (49%) than those children who do use YouTube each week (36%), who are more likely to read weekly or less. [4]

There is a statistical link between higher frequencies of children reading books to themselves and their doing activities off-screen including reading magazines, doing arts and crafts and being read to. In particular, the link between children being read to and their propensity to read to themselves is strong.

The positive effects of reading to children

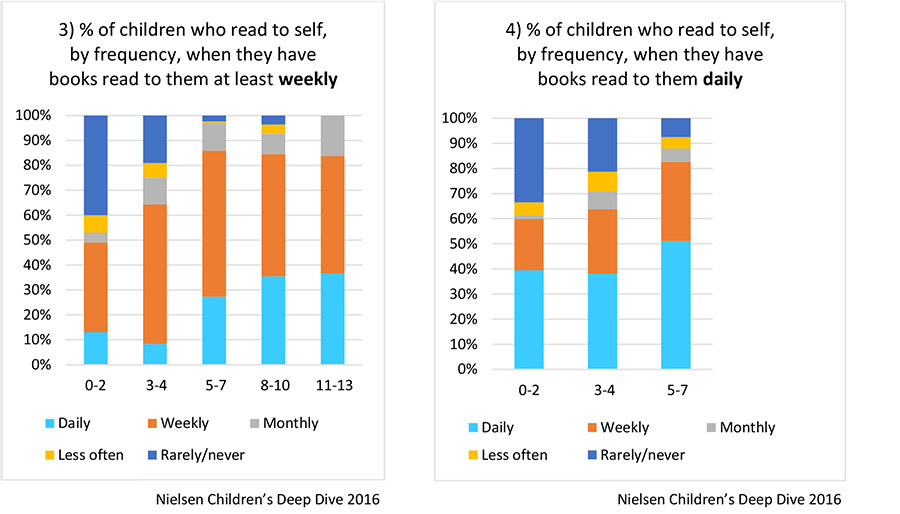

The charts below show that the positive effect of reading to children increases as they get older. Looking at chart 3, at the youngest age group, 0-2 years, we can see 40% who are read to at least weekly rarely/never pick up books on their own. This is because the main way they access books and stories is through others. As the child gets older, we can see the impact reading on at least a weekly basis makes, so that by 11-13, if they are read to at least weekly, none read less often than monthly to themselves and none read rarely or never.

The more children are read to, the more impact it has. Chart 4 shows the huge influence of reading to a child on a daily basis. To illustrate, on chart 3 we see that 8% of 3-4 year olds read to themselves daily when they are read to at least weekly. Chart 4 shows this rises to 38% when read to daily. (As chart 6 shows on the next page, reading to children age 8+ is uncommon and so it is difficult to get a representative sample size to see the impact of being read to at this age.)

It is clear that parents need to give their time and read to their child.

Parents are reading to their children less often

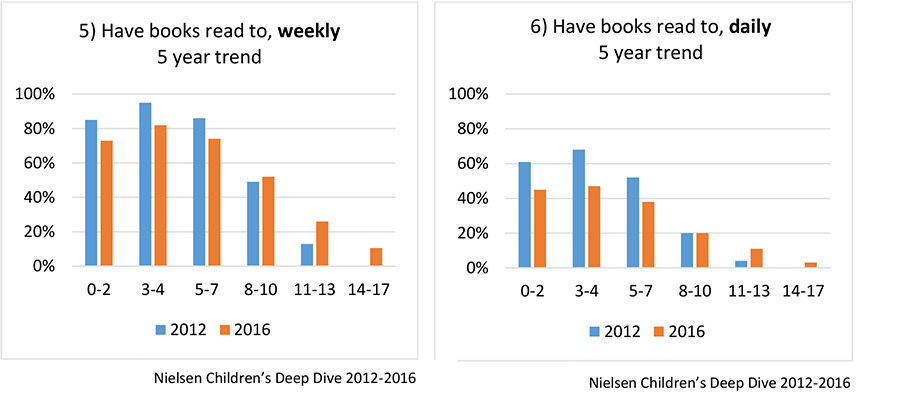

Despite the importance of reading to children, parents are reading to them less often.

When we track reading to children on a weekly basis (chart 5) and a daily basis (chart 6) over the last five years, we see a downward trend at younger ages. Of particular concern is the 0-4 age group, where we see a steady decline. These are such critical years for forming attitudes to reading and stories. The fact is, from birth to seven, children are being read to less often. As Michael Morpurgo commented in his speech at the annual Booktrust lecture in 2016, something is not working. The message about the importance of reading to children is not getting through.

For the first time last year, we asked 14-17 year olds if their parents read to them. 11% are read to weekly and 3% daily. This is an interesting age bracket with a lot of change in a teen from 14 to 17. Of the 14-15 year olds, 14% say their parents read to them weekly; of the 16-17 year olds, 7% say their parents read to them weekly. We also asked teenagers if they would like their parents to read to them, and some would. 22% of 14-15s responded ‘definitely yes’ or ‘maybe’. Since just 14% of parents do read to this age group, there is clearly an opportunity here. [5]

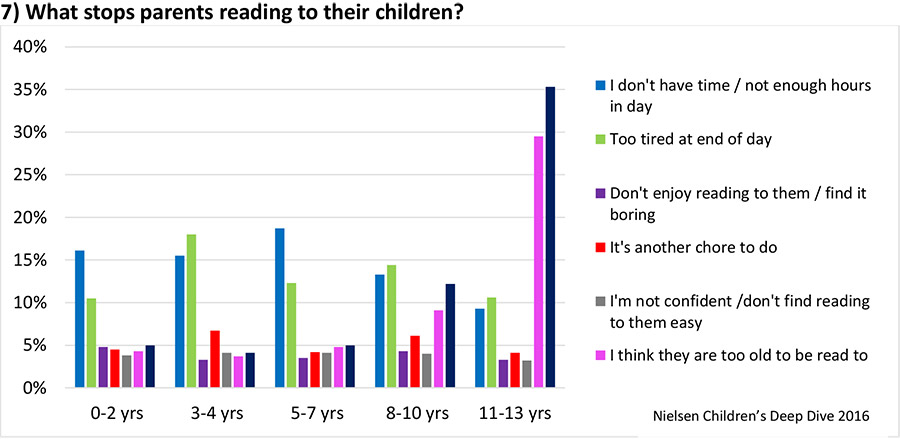

As shown in chart 7, the main reasons parents don’t read to their children are lack of time and tiredness. As children get older, ‘I think they are too old to be read to’ becomes a barrier along with ‘they think they are too old to be read to’, so that by 11-13 years these are the two main reasons. Given 22% of 14-15 year olds said they would like to be read to, we can assume that under 14s would like it, too, and we can conclude that parents’ perceptions might not be reality.

What would encourage more reading?

Parents of 0-13 year olds and 14-17 year olds themselves say ‘finding more interesting books’ would help to encourage them to read more. In 2016, 15,450, children’s books were published in the UK [6]. There is a huge amount of choice but books need to be discovered. ‘A bedtime reading routine’ was also considered a way to help more reading by parents of 0-13s and by 14-17s themselves. It is clear that parents need to be involved in their child’s reading, help them find books that appeal and help them establish and maintain a bedtime reading routine. This will give the reading habit a chance to stick.

The importance of magazines

For many children, reading a book can be a daunting prospect:

‘I don’t really like Harry Potter because it’s just pages full of words and it’s not got drawings’

Boy, 8

Some children prefer magazines:

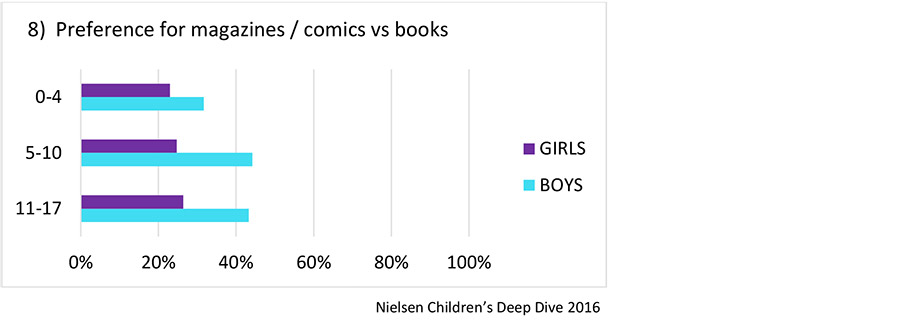

Around a quarter of all girls say they prefer magazines to books. For boys, their appeal is higher. And their importance rises further for those who have negative attitudes to books:

- 57% of children who say they ‘don’t enjoy reading books’ prefer magazines

- 59% of children who ‘don’t think books are cool’ prefer magazines

Magazines offer fun and entertainment for children – and parents see them primarily as a treat. However, they are a treat with benefits [7]. Parents’ second most important consideration when buying a magazine for their child, after the fun and entertainment, is the soft learning it offers: activities, making things and reading. Children are not aware that they are reading when they have a magazine. We might call it reading by stealth.[8]

This mum’s comment about her 7-year-old son is typical:

‘There is no stress of having to read his school book – he just reads without knowing he is doing it’

Barriers at retail

Physical bookshops are very important for children’s book sales:

- 71% of parents of 0-13s and 64% of 14-17 year olds agree that ‘Looking at books in physical shops gives a better idea of suitability than looking online’.

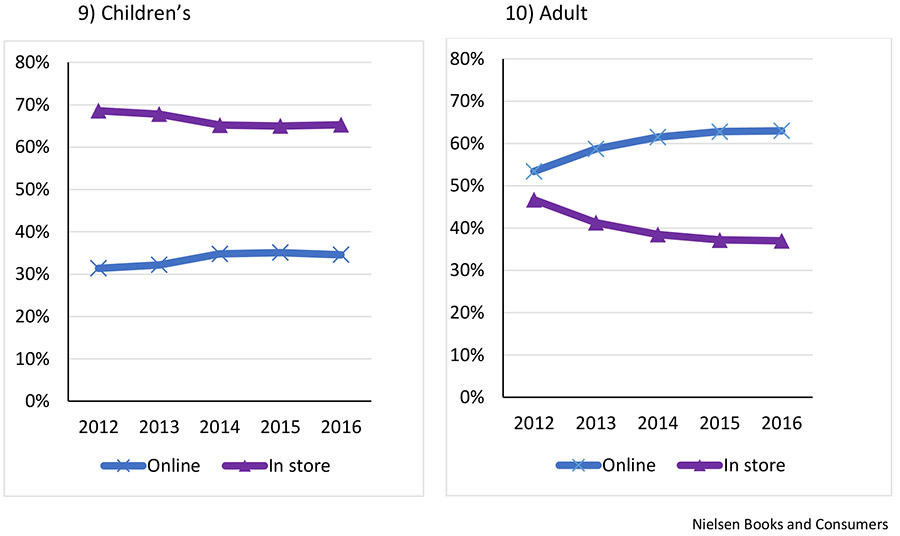

Children’s books are more likely to be bought in physical shops, whereas books for adults are more likely to be bought online (see charts 9 & 10 showing percentage of books bought in physical shops vs bought online):

However, a barrier is simply getting families into bookshops, since visiting a bookshop is increasingly less of a routine and more of a special occasion. Consumers do expect to continue buying in physical shops but they are becoming more demanding of the experience and want to be inspired. A further obstacle to buying books is the low knowledge of parents and children of what is available or suitable. This leads them to look for the familiar and is a barrier to expanding their repertoire [9].

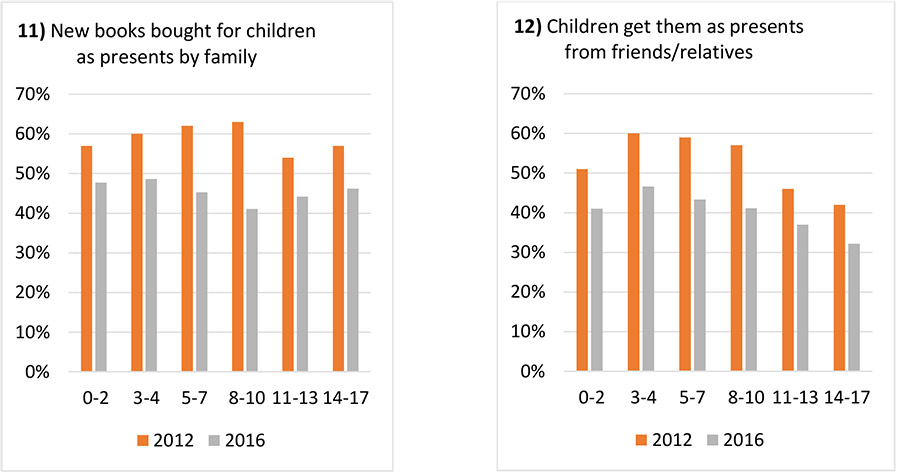

Moreover, gifting children’s books is trending down:

There are similar barriers at retail for magazine sales. Knowing what is available is a key challenge, and 76% of parents find out at the newsstand [10]. Therefore, ensuring magazines stand out is critical. If discovery is mainly at point of sale, then making a sale is dependent on parents going to the newsstand when in store, but parents can choose to avoid it. Parents’ own magazine purchase is becoming less frequent, so this means they set eyes on children’s magazines less often, too. For buying both children’s books and magazines, consumers need help with navigation of the shelves and with selection.

Our 2016 study, Print Matters More, addresses many of the barriers described in this article, and shows that it is possible to turn reluctant readers and buyers into reading enthusiasts and new consumers.

Footnotes

- Nielsen BookScan 2016 vs 2015

- Seymour Distribution 2016 vs 2015

- Nielsen Children’s Deep Dive 2016

- Nielsen Children’s Deep Dive 2016

- Egmont/Nielsen Children’s Deep Dive 2016

- Nielsen BookScan

- Egmont’s ‘Print Matters’ study, 2015

- Egmont’s ‘Magazines for the Early Years’ study, 2016

- Egmont’s ‘Reading Street’ study

- Egmont’s ‘Magazines for the Early Years’ study, 2016